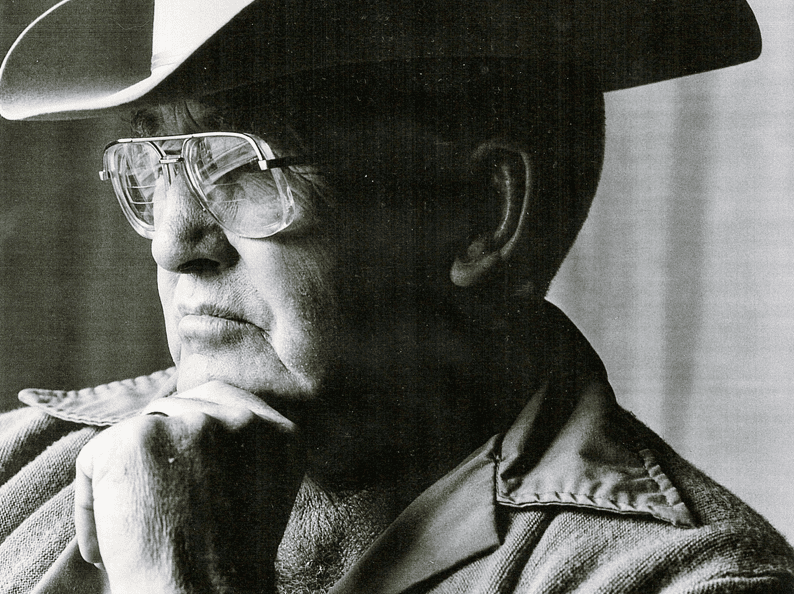

My mother says that as babies, my identical twin sister and I would jibber jabber back and forth, telling each other stories only we could understand. As I got older, my Grandpa May—with only an eighth grade, one-room-school-house education—randomly tossed out big words when I visited him, testing me to see if I knew what they meant.

“Feeling lugubrious today, Laura?”

“I don’t know, Gramps. You got me on that one. What does ‘lugubrious’ mean?”

Pronouncing the word a time or two before revealing its meaning, Gramps would emphasize every syllable, turning it around in his mouth to savor each sound. “Lu-gu-bri-ous,” he’d say with a touch of self-satisfaction. “Lugubrious means to look or sound sad and dismal.”

“Oh, Gramps! That’s a perfect word for me today. Lugubrious Laura. I love it!”

Grandpa taught me other big words, too, like “circumlocution,” “cogitate,” and “prevaricate.” To him, three-syllable words were white diamonds to examine with the focus of a jeweler. Whenever he happened on to a word he didn’t know, my inquisitive grandfather would look it up in the green Webster’s dictionary he kept next to his easy chair in the living room.

As Gramps learned new words, he’d salt them through stories he told from his kitchen table or out in our small-town community whenever he was asked to speak as a dignitary of our town. Later, he sprinkled words like “parsimonious,” “auspicious,” and “erudite” through occasional letters he wrote me while I was earning a bachelor’s, a master’s, and a doctoral degree in English.

Grandpa’s mastery of words, along with his natural affinity for telling funny stories, got him elected Mayor of Jackson, Wyoming, the small town where I grew up. His love of language laid the foundation for my own writing and storytelling abilities. And while neither of us expected me to get a Ph.D. (my “Piled Higher and Deeper,” he called it), I know Gramps was proud of my ever-expanding vocabulary.

My grandfather naturally recognized the power of storytelling to entertain and persuade, but I don’t think he’d be crazy about this digital age of short-and-to-the-point stories in order to hold impatient web readers’ wandering attention. With any audience, once Grandpa got well into his story, he’d often say, “And to make a long story longer. . . .”